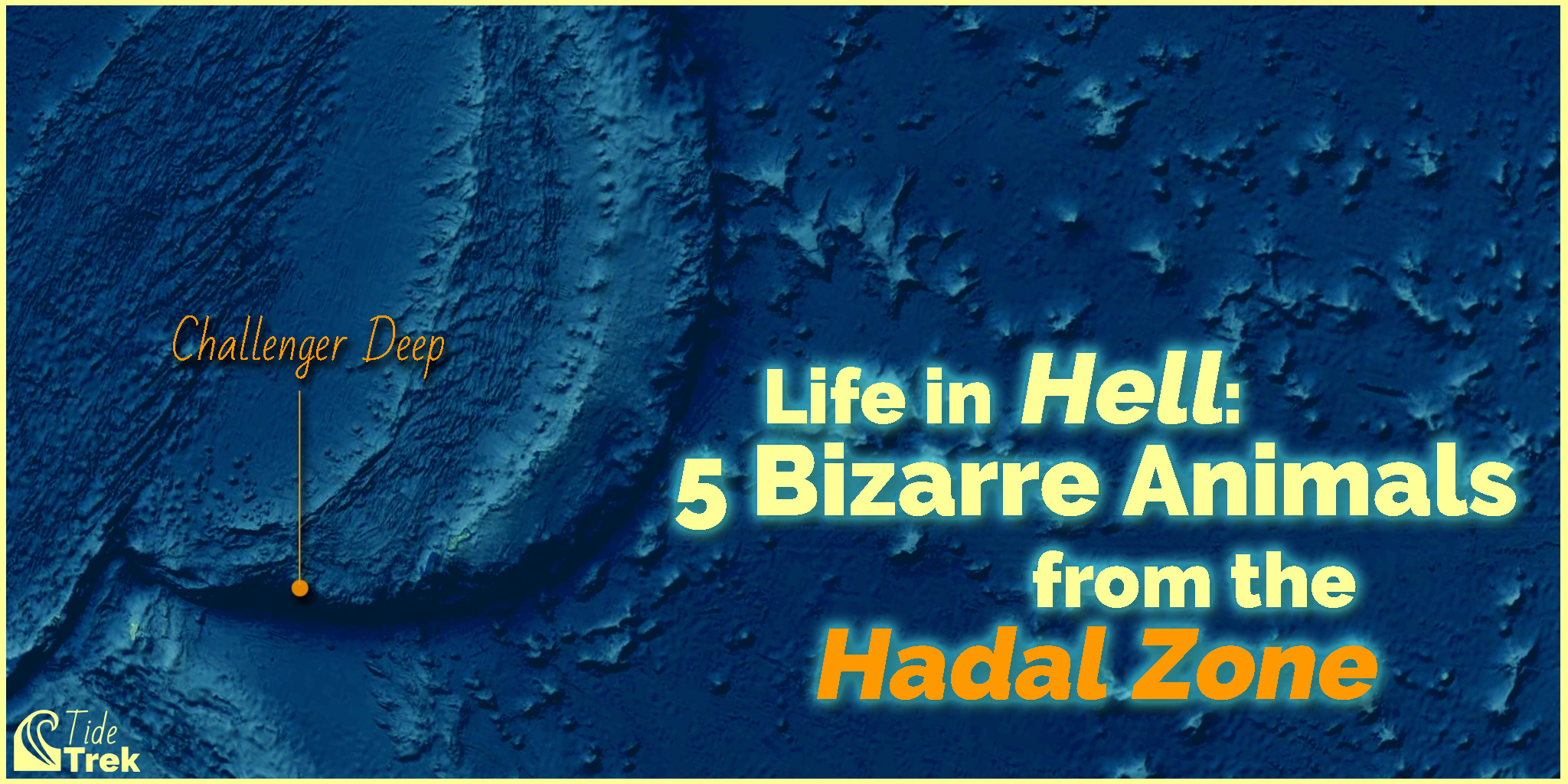

At a whopping 10928 meters (nearly 7 miles!!) the Challenger Deep is the deepest point we know of in the oceans. This point lies at the southern end of the Mariana Trench, the deepest ocean trench in the world. This region of the ocean, known as the hadal zone, is one of the least explored parts of our planet. How do animals from the hadal zone live in such an extreme place?

Not only is it utterly black at these depths (sunlight stopped trickling down all the way up at 1000 meters), but the hydrostatic pressures are immense. At Challenger Deep, they are 15750 psi, over 1000 times the pressure at sea level! That’s the weight of a bull African elephant on every square inch of your body simultaneously!

It’s hard to imagine what could possibly survive in such a hostile environment.

What is the Hadal Zone?

This is the zone of the ocean named after Hades, the Greek God of the Underworld! The hadal zone is reserved for the ocean trenches and covers everything below 6000 meters deep.

And yet, despite the darkness, pressure, and cold, we find that ocean trenches are nevertheless teeming with life. Very strange, baffling (and sometimes scary!) life, but life nonetheless!

Sadly, the denizens of the hadal zone get far less love in the news and social media than their abyssal (4000 m – 6000 m) and bathyal (1000 m – 4000 m) cousins. Anglerfish, dragonfish, and chimaeras are great subjects for Halloween listicles while bioluminescent ctenophores and jellyfish look stunning on camera. Hadal organisms may seem a bit drab in comparison, but they don’t need looks. They’re cool simply because they exist at such ridiculous depths!

So without further ado, here are five organisms that actually live in the hadal zone below 6000 meters!

Animals from the Hadal Zone

1. Grenadiers, the Most Abundant Deep-Sea Fish

Grenadiers, sometimes known as rattails, are a group of marine fish from the family Macrouridae that inhabit the deep-sea from 200 m to 7000 m. As a whole, grenadiers may represent up to 15% of all deep-sea fish (fish that live below 200 m).

Though light is absent in the hadal zone, grenadier species that live here have evolved other means of sensing their environment. All fish have a special sensory organ called a lateral line that senses movement and vibrations in the surrounding water. In grenadiers, this organ is especially well-developed to compensate for the lack of vision.

Hadal grenadiers also tend to be generalist benthic (bottom) feeders that eat a variety of crustacean and amphipod prey. As such, they are particularly attracted to hydrothermal vents and hydrocarbon-rich cold seeps. These features are prominent in oceanic trenches due to the subduction and volcanic activity occurring in them.

2. Snailfish, the Hadal Zone’s Dominant Vertebrate

Snailfish belong to the family Liparidae, a group that contains over 400 species yet remains poorly known to science. They are characterized by tadpole-like bodies and transparent, gooey skin that gives them a rather ghastly appearance!

You can find snailfish anywhere from intertidal zones only a few meters deep all the way down into the Mariana Trench over 8000 meters deep! No other family of marine fish has a depth range this extreme!

The deepest described snailfish species is the Mariana snailfish (Pseudoliparis swirei), which was filmed at 8076 meters in 2016. Since then, a Japanese research crew filmed a new snailfish species at 8178 meters in 2017. This species is still undescribed!

Though the Mariana snailfish only grows to about 30 cm long, it is the top benthic (bottom-dwelling) predator in the Trench, feeding on small crustaceans that inhabit the seafloor.

In fact, these deep-sea snailfish may hold the record for the deepest dwelling vertebrates! The only other contender for this record is the next animal on our list…

3. Abyssal Cusk-Eel, The Deepest Fish Ever?

The abyssal cusk-eel, Abyssobrotula galatheae, may hold the record for deepest fish ever caught. A specimen was trawled up from a depth of 8370 meters (!!) in the Puerto Rico Trench in 1970. However, the net that caught the specimen may not have been fully closed, so it’s possible it was caught at a shallower depth.

Like the snailfish, cusk-eels are also a bottom-feeding marine fish family (Ophidiidae) with gooey skin. Despite the name, cusk-eels are actually more closely related to tuna than they are to true eels.

Though nowhere near as abundant as snailfish in the hadal zone, the cusk-eel is likewise adapted to the extreme depths of oceanic trenches. The gooey texture of cusk-eels and snailfish comes from a gelatinous watery tissue beneath their skin. Combined with the absence of internal airspaces like a swimbladder, this gooey layer of tissue provides both structural protection against high hydrostatic pressure and some measure of buoyancy control.

Apart from snailfish and cusk-eels, there are no other fish we know of that inhabit the hadal zone at these depths. That’s right, these are the only living vertebrates (aside from the occasional human visitor) you’ll find below 8000 meters.

Animals from the hadal zone can only get so deep until it’s too deep!

For fish at least…

Beyond about 8500 meters, fish seem to be entirely absent. However, researchers don’t yet know for certain why this limit exists. The immense pressure at these depths is the likeliest culprit.

For vertebrates like fish, such pressures are so great that proteins themselves are destabilized. Essentially, the molecular machinery inside their cells simply breaks down!

Hadalpelagic fish like cusk-eels and snailfish can counteract this effect by producing a special compound called trimethylamine oxide (TMAO). This compound helps to stabilize proteins against the extreme hydrostatic pressure, but only to a certain point. The greater the depth, the greater the concentration of TMAO necessary to keep proteins from denaturing. Researchers calculate that beyond roughly 8200 meters, the required TMAO concentrations would be too high for the fish’s cells to handle. The result is a natural biochemical constraint on how deep fish can live!

4. Invertebrate Animals from the Hadal Zone: Deep-Sea Prawns

As for invertebrates, scientists once thought the hadal zone was inhospitable to them as well. This does seem to be true for some invertebrate groups you’ll find elsewhere in the deep sea, such as cephalopods (squid and octopus). However, crustaceans have managed to scrape by!

Researchers have encountered the Benthesicymid prawn, Benthesicymus crenatus, up to 7703 meters deep in various Pacific trenches. Benthesicymus is a decapod, which is a crustacean order that includes shrimps, lobsters, crabs, and crayfish. Until researchers discovered Benthesicymus in the Kermedec, Japan, and Mariana Trenches in 2009, decapods were thought to be absent from the hadal zone!

5. Invertebrate Animals from the Hadal Zone: Giant Amphipods

Amphipods are a group of shrimp-like crustaceans (sometimes called “insects of the sea”. They are typically less than a centimeter long. However, the amphipods that live in the hadal zone are 20 times larger, up to 30 cm! Until the University of Aberdeen pulled up several complete specimens on an ocean research expedition in 2012, no one had observed them since the 1980s.

Like the snailfish, we have only just started to observe these mysterious creatures in their natural environment.

The immense hydrostatic pressure at hadal depths would crush most amphipods to a pulp, but these strange giants do just fine! Exactly how the giant amphipods of the hadal zone survive the immense pressure is still unknown for the most part.

At least one species, however, makes its own suit of aluminum armor to protect itself. Hirondellea gigas, which lives all the way at the bottom of Challenger Deep, extrudes a layer of aluminum hydroxide gel over its exoskeleton. Because amphipods are detritivores (scavengers), they end up consuming a lot of sediment from the seafloor. H. gigas extracts aluminum ions from the mineral-rich sediment of Challenger Deep through chemical reactions in its digestive system. Once exposed to the alkaline seawater in the deep trench, the aluminum ions chemically transform into the protective aluminum hydroxide gel!

So much about life in the hadal zone is still unknown…

As you can see, there are several interesting species that can survive the extreme pressure and darkness of the hadal zone. There are even more creatures beyond the ones I’ve mentioned here that still remain undescribed! Researchers have observed deep-sea sponges, bivalves, and anemones in the deepest ocean trenches too, but we still know very little about them.

Given that researchers only discovered some of the species on this list in the last 10 years, there are probably countless more organisms we have yet to discover! The hadal zone comprises less than 1% of the planet’s total seafloor, but over 40% of the total depth range. That’s a perfect combination of isolation and environmental uniqueness to drive the evolution of highly-specialized lifeforms.

Who knows, perhaps by next Halloween there will be some new species on this list!

If you want to keep updated on the content I produce here at Tide Trek, please consider signing up for my mailing list. At the end of each month I prepare a little round-up newsletter that summarizes new articles I’ve written, and content I’ve curated covering all things water sports (even some cool marine science too!)